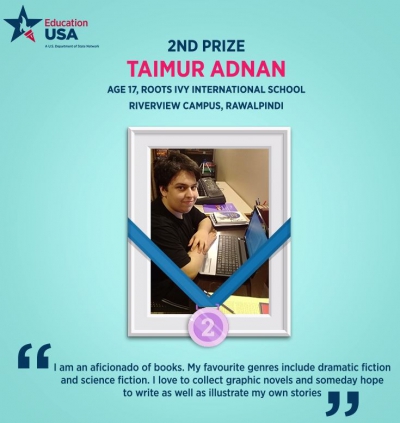

Earlier this year, we ran a Creative Writing contest for young writers between the ages of 16 and 18. It gave us the opportunity to read through hundreds of excellent submissions received from all across the country. Presented here is Taimur Adnan’s submission which was awarded second place in the contest. He is currently a student at Roots Ivy International, Riverview Campus in Rawalpindi.

Life is a fickle friend.

One day you’re the ‘in’ thing, the next, you’re ‘out’.

You could be flying high and then suddenly you find yourself descending faster than you can say, “Shiny shoes”.

For all my loyal fans, let me reassure you that I am not talking about myself here. *Lollywood still needs me and there are many more stories to tell.

For today, there is one particular story that I would like to share. Perhaps it will encourage you to pursue your dreams no matter what the cost or maybe it will teach you a powerful lesson about how fleeting life can be.

It all began in the middle of October 2012 in the bustling and crowded streets of Peshawar, a city in Pakistan located close to the border with Afghanistan; home of the Khyber Pass and Qissa Khawani Bazaar, among other famous landmarks. There, among the latter aptly named market, also known as the ‘Storytellers Bazaar’, while trying to soak up the local culture for a new drama script I was working on, I saw a crowd of men gathered outside a roadside eatery.

Being a man with ink for blood and a nose for stories (profession: scriptwriter), I crossed the busy street while narrowly avoiding being hit by a rickshaw, whose driver nonchalantly swerved his vehicle and continued on his speedy mission. Wading through the crowd of turbaned and bearded gentleman, my curiosity was at a peak. That’s when I saw him: a boy of medium height and fair skin, barely 20 years old, with hair the color of wheat and eyes as green as emeralds. He looked up at me and grinned with perfect white teeth:

“Salam sahib! **Boot polish karoon?”

The other men jostled me but I was too mesmerized by his innocence and beauty to care and quickly took my place on a makeshift, wooden chair.

The young fellow laid out his tools of the trade: a wooden storage box (which had seen better days) with a footrest, horsehair brushes, cloths and assorted polishes and crème containers.

I placed my dusty and scruffy shoe on the footrest and he began to expertly brush and polish it until it shone like ebony.

While he worked, he kept up a steady chatter about everything, from the weather to where I could get a good deal on winter clothing (a relative owned one of the roadside stalls in the market). He talked about everything under the sky except himself. Being a writer by profession, I knew that there was more to this youth than meets the eye. As he gave a final, rigorous polish to my shoes, I took out my wallet.

“How much?” I inquired.

“Whatever sahib wants,” he replied sincerely.

I took out Rs. 100 and handed it to him.

“***Shukriya!” he grinned and pocketed the amount.

Just then, there was a loud commotion and the gentlemen around us dispersed like dandelion seeds in the wind.

“Wali!” another young man bounded over and grabbed him by the arm. “Hurry! The police are on their way! Run!”

As I looked on in shock, the shoe shiner dumped his tools in the wooden box, gave me a jaunty salute and melted into the crowd.

The police ran past me but it seemed that the young man had taken off at a great speed and could not be apprehended.

I smiled to myself at the strange encounter as I walked back to my guesthouse, vowing to find the talented ****bootwallah once again on the streets of Peshawar.

Two days passed as I searched for my muse but he was nowhere to be found in the Qissa Khawani Bazaar.

On the third day, I stopped by the clothing stall he had recommended. Just when I had almost bought a synthetic fire-engine red sweater for my daughter, I saw him buying bananas.

“Wali!” I called his name and he looked around in fear. When his eyes rested on my face, he relaxed and sauntered over to shake my hand.

I invited him for a cup of tea and he looked warily at me until I told him that I did not mean him any harm and just wanted to talk.

We walked over to a small dhaba (roadside restaurant) and ordered doodh pati chai (tea with milk) and a plate of pakoras (fritters). He devoured the snack so I asked for some more and we began to talk.

He told me about how his family lived in Kabul in Afghanistan, where his father was a professor at a university and his mother was a seamstress. But then, the Soviet invasion took place in 1979 and turned their world upside down. He wasn’t born yet but his elder brothers died in the fighting. His family had no choice but to put on a brave face and move, along with their few belongings, to Pakistan.

I thought of the millions of other Afghanis who had crossed the border into Pakistan and settled in refugee camps.

Wali was born in a refugee camp but his mother died in childbirth and his father soon succumbed to grief and heartbreak when the young lad was just six years old. Since then, he was raised as an orphan by his father’s tribesman.

I asked him why he had not returned home now that the Taliban were being pushed back.

“Where is home, sahib?” he questioned earnestly. “There is nothing for me in Afghanistan but the fear of a brutal death and rubble where my family once lived. No, sahib,” he continued, “I feel safe here, even though it is not a perfect life. But I make an honest living.”

My eyes welled up with tears as I thought of the struggles of this fresh faced young man with the barest hint of whiskers on his upper lip.

“How did you begin polishing shoes?” I asked.

Wali, whose name means ‘helper’ or ‘protector’ in Arabic, told me about how he had stumbled across an old man in the bazaar who had taught him how to shine shoes and make a living. Although the old man did not provide fair wages to Wali, he did leave him with his tools before he passed away. Since then, Wali had been moving from one place to another, in the hopes of making the bare minimum while hiding from the authorities. Many of the Afghanis living there were not residents or citizens of Pakistan and as such, they did not have the proper rights. They were categorized as ‘IDPs’: internally displaced persons. I wondered if being labeled in this way was supposed to make them fit into society or just widen the gap.

As we swallowed our last cup of tea, he reached into a satchel and took out two thin, children’s books. One of them was on the English alphabet and the other was a book about numbers. He had bought them with his meagre earnings as he wanted to learn.

“Look sahib,” he pointed out. “W is for watch, water and Wali!”

I couldn’t help but smile at his triumphant grin.

As we parted, I offered to pay towards his education but he refused and pushed away the money in my hands.

“Just pray for me, sahib. Make dua (prayer) that one day Wali will be rich and famous.”

“Wali the bootwallah from Afghanistan,” I laughed.

“No, sahib. Wali the bootwallah from Pakistan!”

Once again, he shook my hands and gave me a salute.

“Allah hafiz (May God protect you),” he proclaimed, before turning away.

“And you,” I murmured as I walked back to my life.

A year passed and I did not get a chance to revisit Peshawar: such was the nature of my ‘glamorous’ job that it kept me from pursuing other interests.

In late September, 2013, I was having tea at home with the television droning away in the background. Suddenly, I heard the words ‘bomb blasts’ and ‘Qissa Khawani Bazaar’. I jumped up, spilling my tea and watched the horror unfold on the screen. Twin blasts had occurred at the market, killing over 41 people and injuring over 100 more.

I sank to my knees and prayed for the bootwallah.

“Allah hafiz (May God protect you),” had been his final words to me. I wondered, through my tears and fervent prayer, if, like his namesake, he had found a protector today: Wali the bootwallah…from Pakistan.

*Pakistani cinema

**Polish your shoes?

***Thank you

****Shoe shiner